Instead of 'jonesing' for a never to be again John Phillips' editorial in that other mag...I get the rest of the story from none other the MAN himself......thank you ,off to the second installment.

Brian

Photography Courtesy the BRE Collection

After the final hillclimb of the 1964 international racing season at Sierre-Montana in Switzerland, only a few races remained on the FIA calendar: the Tour de France, the two circuit races at Monza, Italy and Bridgehampton in the U.S.

Bob Bondurant had won the difficult Swiss hillclimb driving one of Shelby’s potent, lightweight Cobra roadsters. Bondo’s surprise victory against Ferrari’s ace hillclimb champ, Ludovico Scarfiotti, in one of Enzo’s latest Series II GTOs had added nine crucial points to the colorful Texan’s tally in the battle for the World’s GT Championship. It also kept his team alive for what should have been their final encounter: a blistering 3-hour sprint a week later on the high banks of Monza at the Coppa Inter-Europa.

It never happened.

After Bondurant’s hillclimb win, just 6.4 points separated the two remaining protagonists for the World Championship title. Enzo Ferrari and Carroll Shelby had fought bitterly over the GT crown since their teams’ first confrontation at the Daytona Continental in January.

Aston Martin, Maserati and Jaguar–Ferrari’s main competition in the previous two seasons–had been rudely shunted aside in the fierce battle between the nascent Cobras and Ferrari’s well-established world champions. Even Ford’s new GT40s, which had entered the series midseason, were no match; serious development problems had sidelined them at almost every event they entered. In the meantime, the Cobras were taking up the slack for Ford.

In their months-long war on two continents, Shelby’s Cobras and Ferrari’s GTOs were both so dominant that the competition had been forced off the podium at almost every race in which they clashed. Each team had earned just enough points to qualify for the crown, and the winner at Monza would prevail.

Everything possible in both camps was being readied for the final confrontation at Monza, as that race was going to be the deciding factor. Bridgehampton, the last date on the FIA calendar, was essentially an inconsequential finale to the season because the winner on the Italian supertrack would have already secured enough points to put a lock on the championship.

The grueling 10-day, 3600-mile Tour de France, scheduled two weeks after Monza, was almost certainly a given for Ferrari. Because of the purposely short times between its official checkpoints, the Tour was essentially a wide-open road race on public roads that included stops for timed circuit races on each of France’s major race tracks. Shelby had neither the resources nor the network of dealerships across the three countries involved to service his cars during the 10-day-long “tour.” Ferrari did.

Shelby, being a realist, knew his team’s chances of winning the Tour were slim, but he figured he could still beat Ferrari for the championship if he won at Monza. As it turned out, the Cobras actually led the Tour for the first couple of days, but with minimal support available from Shelby’s handful of mechanics, who also had to race from checkpoint to checkpoint, they faltered and dropped out.

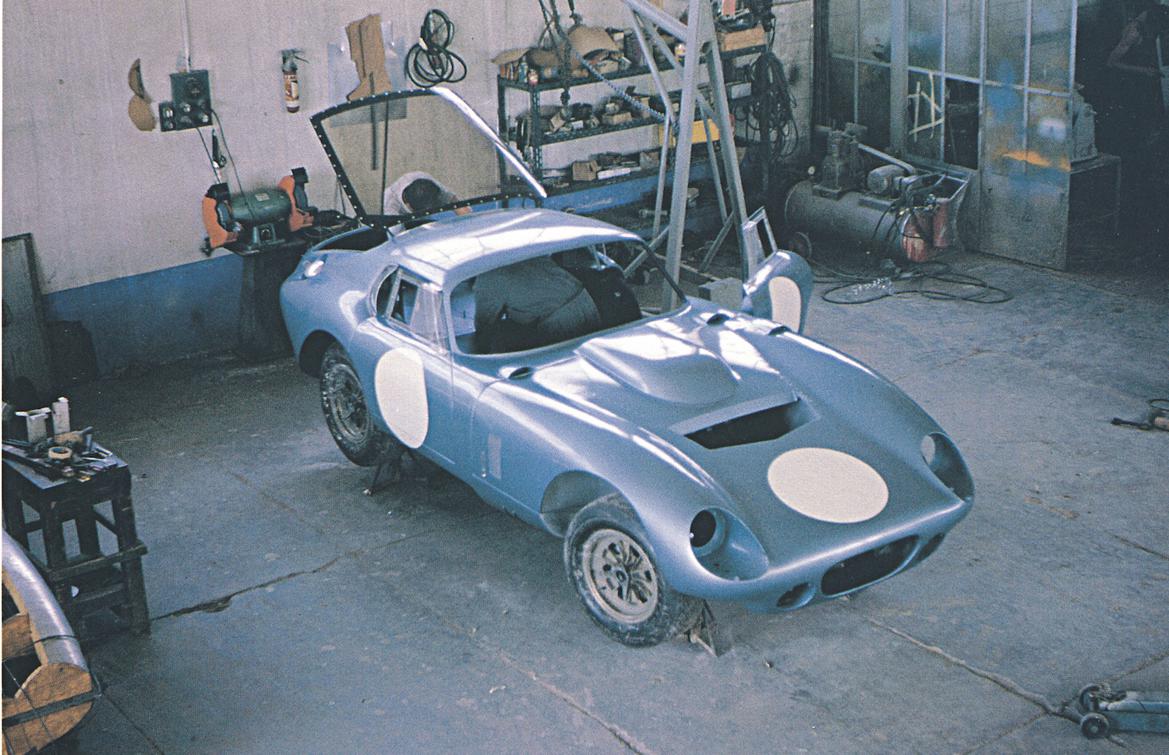

Carrozzeria Grand Sport’s ace fabricator “Sam” Cavazutti, the only man in the shop who spoke some English, with the partially completed body of CSX 2286. The extra 3 inches added to the Daytona Coupe’s frame becomes evident.

Shelby had been the apparent underdog from the start of the 1964 season. His cars and team were unfamiliar with the European circuits, and he had only one of his controversial new Daytona Cobra Coupes ready for the opening round against Ferrari’s three GTOs at Daytona. Much to everyone’s surprise, the slippery Cobra Coupe was the class of the field, easily leading the race until a refueling fire in the pits sidelined the car, giving Ferrari a lucky break for the start of the season.

A few weeks later, the tables were turned: Shelby’s only Daytona Cobra Coupe won the 12 Hours of Sebring, putting the American team in the lead for the championship. Since the FIA awarded points for each event based on its difficulty–a simple formula based on time and distance–Shelby’s win at the 12 Hours of Sebring easily countered and surpassed the few points that Ferrari had secured at the shorter Daytona Continental. It was actually this Sebring victory that convinced Henry Ford II to convert what had largely been Shelby’s privateer effort, backed mainly by Goodyear, into a fully funded factory team for the remainder of the season.

Ford’s GT 40 was expected to be competitive soon after Sebring, but that plan kept getting delayed by development problems. Ford’s reputation was totally on the Cobras.

The Cobra Daytona Coupe’s speed against the well-proven Ferrari GTOs had been a surprise to all but a few true believers within the Shelby team, most of whom had serious initial doubts about the car’s potential. That changed after Daytona–even though it DNF’ed because of the pit fire. The Coupe’s amazing speed and performance had welded Shelby’s tiny team into a force to be reckoned with.

A second Daytona Cobra Coupe–with a body hurriedly built in Italy was prepared for Le Mans, so there would be a two-car Shelby American entry for the French classic. Even though CSX 2287–the first California-built Daytona Coupe, driven by Chris Amon and Jochen Neerpasch–led the 24-hour enduro for almost half the distance, it was unexpectedly disqualified by the race officials after a heated Ferrari protest. The reason: The Cobra Coupe’s generator belt had loosened throughout the long hours of the race, and with no charge from the generator, its battery didn’t have enough amperage to start the car after a pit stop.

It didn’t matter; Bondurant and Dan Gurney in the first Italian-bodied coupe had been shadowing the front-runners and quickly swept into the lead when Neerpasch’s engine wouldn’t start.

Bondo and Dan won the GT class, but not without some problems of their own. Their Cobra Coupe was so fast that it might well have won overall against the Ferrari prototypes, but a stone through its oil cooler in the middle of the night caused just enough delay from repairs to kill what would have been the car’s greatest-ever win. No GT class racer before or since has ever won overall at Le Mans, but the GT win put Shelby’s team well in the lead for the GT crown.

By the end of June, Shelby had two more regular Daytona Cobra Coupes being prepared for the Italian showdown at Monza in September. With a total of four Coupes entered, he intended to win the GT championship by crushing the Italians on their own turf.

Never one to cancel thoughts of excess, Shelby also ordered a fifth, even more powerful coupe built for the final race. It would be powered by an experimental all-alloy, 390-cubic-inch engine based on Ford’s mighty iron-block 427s used in NASCAR.

Because the larger-but-lighter, specially cast alloy 390 engine wasn’t one of the officially homologated, production-based 289 “small blocks” as specified in the rules, Shelby’s Monza ringer obviously wouldn’t comply with the GT regulations. But that didn’t matter: That wasn’t its purpose. Because this prototype coupe wasn’t a real “production” GT Daytona Cobra, this special weapon’s wheelbase had been stretched by 3 inches in Shelby’s shop in California to accommodate the larger engine and fuel tank. CSX2286, like the other four cars, had its special “Monza” body crafted in Modena by Carrozzeria Gransport.

These changes required it to run in the faster Prototype class against Ferrari’s latest mid-engined, 3-liter LM coupes. The 390-engined monster, now being called the Monza Coupe, was built especially to squash Ferrari’s LM Prototypes for the overall win at Monza–a bitter payback for the Ferrari team’s niggling protest at Le Mans on the minor detail that had sidelined Amon and Neerpasch.

With just days until Monza, Enzo Ferrari was in deep trouble. He knew from experience that Shelby’s four Daytona Cobra Coupes would be faster than his 250 GTOs. Because of this, he’d been trying since the first race of the season at Daytona to convince the FIA to legalize his latest, mid-engined 250 LMs–now with 3-liter engines–as “production GTs.”

However, the competition board wasn’t going along with it. Only a handful of Ferrari’s radical LMs had been built, and the latest FIA rules required 100 examples to be completed and running to qualify as “production” GTs. No deal.

Had the newer 3-liter LMs been homologated as real GTs, Ferrari might well have had an excellent chance of winning at Monza, but by the end of the summer it was clearly evident that this wasn’t going to happen. Enzo was desperate. Losing at Monza–the most important race of the season in Enzo Ferrari’s home country and in front of the rabid Italian fans–would have been far worse than personally insulting the Holy See in Rome! No, Ferrari couldn’t afford the national dishonor of losing the GT war and the World Manufacturer’s Championship to the brash Texan.

As the second most respected entity in Italy, Enzo Ferrari commanded tremendous power in Italian politics and racing. He and his thousands of Ferrari loyalists viewed the matter of victory at Monza as a point of Italian honor; they simply could not afford to lose to the Americans.

Ferrari secretly contacted the Automobile Club d’Italia, the organizers of the Monza race, and called in a very heavy favor. He convinced the club’s organizers to pressure the FIA’s contest board once again into homologating his mid-engined 330 LMs as GTs. The FIA of course refused, as only three had been built. The Automobile Club then used the refusal as reason to cancel the FIA’s sanction of the race.

Without the official FIA sanction, it mattered not who won at Monza; the “winner” would receive no points–and Ferrari, because of his expected win on the Tour de France, would edge Shelby by 10.8 points and win the championship by default.

With no official sanction for Monza, it was pointless for Shelby American to even appear. Jaguar and Aston were already so far out of the running that they had no plans to attend, either. The media conveniently wasn’t informed of this minor detail, so the race still took place, but the thousands of Tifosi who came to spectate were never made aware of the American team’s “withdrawal” until after the start. By then, the Automobile Club d’Italia had already raked in the millions of lire required for solvency.

Ferrari, of course, entered his full team, including the trick “GT-banned” LMs, as there was no sanctioning body to prohibit them. As a result, Ferrari “won” at Monza.

Ferrari also easily won the Tour de France, as expected, and put the 1964 World Championship GT title in the record books. Then he quietly announced his formal withdrawal from GT racing for 1965. Enzo Ferrari knew his 250 GTOs were obsolete against the faster Daytona Cobra Coupes, so there was no point in continuing. He did go back to the FIA to get them to limit GT car engine size, starting in 1966. That eliminated any possible future threat from the Ford-engine Cobras or GT40s.

In the years ahead, Ferrari knew the records would show that he had won the GT championship in 1964 and there wouldn’t be an asterisk to explain why. Instead, for 1965 Enzo Ferrari grandly announced he would only contest the Prototype classification in international competition. His latest mid-engined P3 and P4 cars were already in the final development process. His goal: Defeat Henry Ford’s latest 427-powered MkII GT40s.

Note the grace that the 3-inch-longer wheelbase adds to the almost complete Monza “Super Coupe” body. This detail made it illegal to race in the FIA’s strictly homologated GT class, where stock chassis dimensions were required.

As a result of the Monza cancellation, the stillborn 390-powered Monza Coupe–chassis No. CSX 2286–never ran with its larger, lightweight engine. Its longer body had been finished at Carrozzeria Gransport in Modena, and its internals were hours from completion when the word came down that there would be no race.

Instead, the almost-finished coupe was shipped back to America, where the chassis was shortened by the 3 inches that had been added. A regular race-prepped 289 engine was reinserted.

As a result of all the extra work, CSX 2286 was the last of the series of six Daytona Cobra Coupes that were built. Because of its late debut, it only raced once: at Le Mans in 1965, finishing second in class. It’s now owned and raced in vintage events by Rob Walton.

For the 1965 season, Shelby’s six Daytona Coupes were “loaned” to the U.K.-based Alan Mann Racing team. There, running against Ferrari privateers and underfunded competition from Aston Martin and Jaguar, Alan Mann Racing easily won the Manufacturer’s GT title for Shelby American. As important as that achievement was, the real high point of the Daytona Cobra Coupe’s success was in ’64. But now only the records remain.

Even more intriguing than the 1964 season’s very public Cobra/Ferrari war was an earlier, much quieter battle ongoing during the final months of the ’63 season–this one internally at Ford headquarters in Dearborn, Michigan. Few now remember that just before the intense 1964-’65 seasons began, Henry Ford II actually tried to buy Enzo Ferrari’s entire operation. Not surprisingly, the deal between the two titans of industry fell apart, and Ferrari was eventually acquired by Fiat.

Instead of backing down on his intent to win the World’s Championship, the Deuce purchased the talent of brilliant English race car designer Eric Broadley, along with his plans and rights to his just-completed Mk6 Lola GT. That car, rebodied and refined under the leadership of Ford of England’s design executive Roy Lunn, became the GT40.

CSX 2287, with Bondurant and Gurney, then went on to lead the race a few weeks later until disqualified. The second, Italian-built Daytona, number CSX2299, which had never turned a wheel in anger until it was rolled onto the starting grid at Le Mans, won with Bondurant and Gurney at the wheel.

Henry Ford II had expected his newly acquired Broadley/Lunn design to be fully developed and winning within months of purchase, but it was not to be. The car had obvious technical potential, with its mid-mounted engine, better brakes and improved Indy-developed GT40 289 engine, but it lacked serious, time-consuming development.

Shelby’s Daytona Coupes, in spite of their ancient Cobra roadster-derived chassis, were still faster, more aerodynamically stable and, most importantly, more reliable. Broadley’s entire operation, renamed Ford Advanced Vehicles, became Ford’s European race headquarters in Slough, England. It was kept as a future European base of operations under the leadership of famed team manager John Wyer. FAV was responsible for Ford’s 1964-’65 racing seasons and the production of customer GT40s, but the actual development and redesign of the radical, larger-engined Mk II version of the GT40 was moved to Dearborn.

Because Ford’s main involvement in American racing was in NASCAR, its management structure was entirely familiar and comfortable with the highly competent and successful Holman & Moody operation, based in Charlotte, North Carolina. It was assumed internally that the new “American-designed” Mk II Ford GT40s would be developed and raced in Europe under the Holman & Moody banner.

At this time, the tiny Shelby American team in Venice, California, was–although Ford-backed–essentially a second-string operation. Most at Ford thought this substitute team of quasi-privateers with Ford-powered Cobras would eventually be replaced by the GT40s of the mighty Ford/Holman & Moody team.

It didn’t work out that way, as the Charlotte-based NASCAR team wasn’t entirely comfortable or successful in developing Ford’s sophisticated, mid-engined road racers. Shelby’s operation, on the other hand–led by racing’s now-legendary Chief Engineer Phil Remington–had proved conclusively with its still-controversial Daytona Cobra Coupes, that it had not only the technical expertise to develop a winning car, but also the hands-on experience at the world’s most difficult circuits to defeat Enzo Ferrari’s finest at their own game.

Shelby Crew Chief John Ohlsen checked some details on the 390 on its arrival from California. The lightweight big-block for Shelby’s Monza Prototype weighed little more than the iron-block 289s used in the regular GT bodied Daytona Coupes. Top speeds were expected to be 220 miles per hour.

Even with Shelby’s moral success in 1964, within Ford there was still a powerful management faction loyal to Holman & Moody and that team’s vast experience with Ford’s 427 NASCAR engines. Since Ford’s engineers had already decided that the sure way to beat the Ferrari P4 prototypes in the coming season was to re-engineer the GT40 chassis to accept the huge NASCAR engine, they also figured it would probably be best to stay with their familiar Charlotte allies.

Countering this internal mindset was an equally loyal but much smaller faction, led by Ford account exec Ray Geddes. He believed Shelby’s team would be best to take the Mk II GT40s into action against Ferrari. Geddes was pretty certain that Henry Ford II would eventually see things his way and began to lobby Ford’s opposing management group to give the GT40 development/race contract to Shelby.

As part of his plan to clear the Shelby shop of any “distractions,” Geddes also arranged to send Shelby’s Daytona Cobra Coupes to the U.K. so they could be raced by Alan Mann in the GT class in ’65. He understood that Ford management didn’t want any “revitalized” Cobra Coupes competing against its GT40s.

Ken Miles, Shelby’s lead development driver, actually believed the Daytonas would be faster–and, most importantly, more reliable–than the relatively new GT40s. He had begun his own quiet, well-intended, “unofficial” internal conversion of one of the Daytonas so it could be tested directly against Ford’s latest iteration of the GT40. He had already equipped one Daytona with the latest, more powerful, and lighter alloy version of the GT40 small block and its improved, multi-piston brakes when the plot was “discovered” by Remington. Miles was severely reprimanded and the car was dismantled.

Shelby, too, had a contingency plan. Still smarting from Ferrari’s political “win” of the 1964 World Championship GT title and the uncertainty of acquiring the Holman & Moody contract from Ford, he quietly decided he’d better have a hole card in case he wasn’t awarded Ford’s GT40 program as Geddes had promised. Shelby personally wanted to lead the charge against Ferrari in the coming 1965 battle for the Prototype championship. Knowing that the ’65 GT assault on the class title would be ably run by Alan Mann Racing in the U.K., Shelby decided his plan for 1965 would be yet another Super Coupe. This time, though, it would have an entirely new shape that formulated on everything learned with the Daytonas in ’64. Best was the plan to use Ford designer Bob Negstad’s newly designed MkII Cobra chassis. Negstad had been responsible for penning the ultra-sophisticated suspension of the GT40. This new Cobra Coupe would eventually become known as the Type 65 “Super Coupe” designed specifically to defeat the P4s on Le Mans superfast Sarthe circuit in 1965.

To be concluded in the second installment.

Instead of 'jonesing' for a never to be again John Phillips' editorial in that other mag...I get the rest of the story from none other the MAN himself......thank you ,off to the second installment.

Brian

A couple of corrections:

Only the 1st Ferrari 250LM had the 3-liter engine (the 250). All subsequent 250s actually had the 3.3-liter engine (the 275), although they were always called "250LM." There was never a 330LM based on the 250LM, but there were three 330LMBs built in 1963, combining the classic GTO front end with the then-current 250GT Lusso from the windshield back.

The Ferrari P4 didn't come along until 1967. It was a further development of the P3. Ferrari's 1965 prototype racer was the P2, which were equipped with the 275 (3.3-liter), 330 (4-liter), and 365 (4.4-liter) engines.

Displaying 1-4 of 4 commentsView all comments on the CMS forums

You'll need to log in to post.