Photography Credit: Dave Green

Story by Steven Cole Smith • Photography as Credited

Photography Credit: Dave Green

First, there’s that engine.

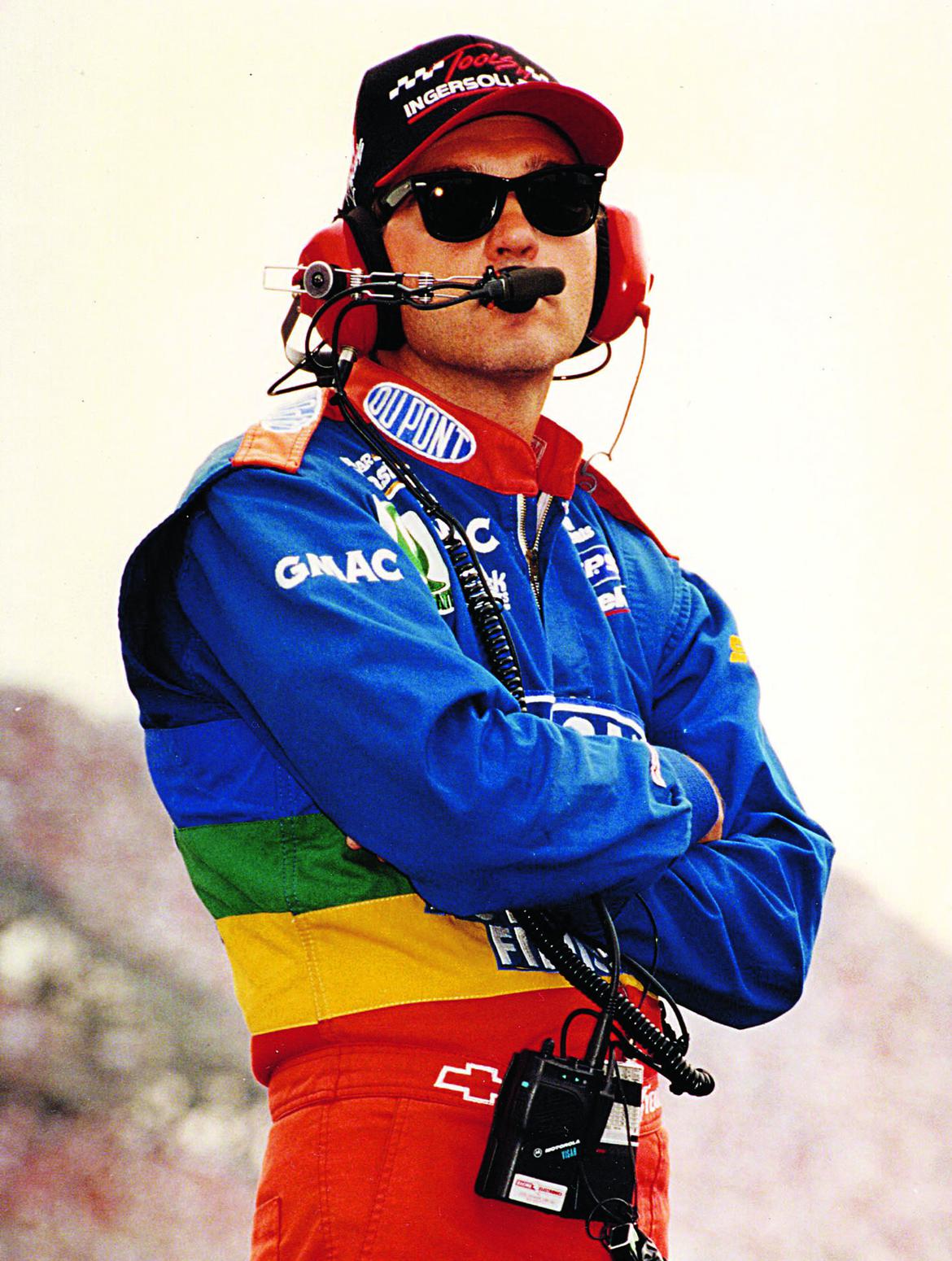

Yes, of course this 1966 Chevrolet Corvette is gorgeous inside and out. And yes, of course its owner and driver is Ray Evernham, who won three NASCAR Monster Energy Cup championships and 47 races with driver Jeff Gordon at Hendrick Motorsports.

But hearing Evernham tear down the back straight at Sebring International Raceway, the Corvette’s 427-cubic-inch big-block V8 at full song en route to a class victory in the Historic Sportscar Racing series event, you overlook for a moment how pretty the car is and how famous its driver has become. You just listen.

Nothing against the pack of Porsche 911s trailing Evernham’s Corvette, but when you’ve grown up falling asleep every night to the soundtrack of an American V8 playing in your head, nothing else compares.

Once you know the pre-NASCAR history of Ray Evernham, you won’t be surprised he’s driving a race car instead of working on it. That was always the plan: Sure, Evernham liked working on cars, but he wanted to be a driver. That’s probably why, in late 1991, he went to work for Alan Kulwicki, the last owner-driver to win a Cup championship, and likely the last one who ever will. But their two very strong personalities clashed, and Evernham quit after six weeks.

But by then, though, Evernham knew he wouldn’t be able to make a living as a driver, a painful and lasting lesson dealt by a mistake he made on track–and a very solid concrete wall. More about that in a moment.

After Evernham split with Kulwicki, Ford latched on to him and placed him with Bill Davis Racing. There he’d be working on an Xfinity team with Jeff Gordon, a young driver Ford had big plans for. When Gordon suddenly–and, arguably, unprofessionally–jumped to Chevrolet and Rick Hendrick’s team, Evernham followed.

The first Cup race for Gordon and Evernham was the final race of 1992, the Hooter’s 500 at Atlanta Motor Speedway. It also happened to be Richard Petty’s last race, and the race that locked up Alan Kulwicki’s season championship. Six months later, Kulwicki would die in a plane crash.

After learning the ropes in 1993, Gordon and Evernham began winning in 1994–and they didn’t stop. The No. 24 DuPont Rainbow Warriors Chevrolet won those 47 races, qualified on the pole 30 times, and won three championships. Perhaps themost startling statistic was that Gordon finished in the top five a remarkable 116 times in 218 races. In endurance events–and every NASCAR race is an endurance event–consistency is crucial, and the Hendrick car had it.

It didn’t hurt that Evernham was an innovator. NASCAR legend Junior Johnson once said Evernham was the smartest crew chief he’d seen. Of course, his ideas didn’t always pay off: NASCAR levied what was then the largest fine ever assessed, $60,000, for an unapproved front suspension part the team used on Gordon’s car for a race in 1995.

Dick Berggren, former editor of Stock Car Racing and Speedway Illustratedmagazines and longtime TV and radio broadcaster, recalls peeking into Evernham’s garage before qualifying at Daytona. It was a chilly day, and Evernham had stationed four pit crew-members beneath the jacked-up car, each with an electric hair dryer, warming up the grease in the wheel bearings and axles. “I hurried up there with my camera and tried to get a shot to put it on the air. Ray ran me out of there. He said, ‘I work my ass off to find an advantage and you want to tell everybody about it!’”

“Ray ran me out of there. He said, ‘I work my ass off to find an advantage and you want to tell everybody about it!’”

Evernham, Berggren says, was the “most cerebral crew chief we had. He did his homework, he studied, he worked hard, and he was good at everything he did.”

Photography Credit: Dave Green

Photograph Courtesy NASCAR

Photograph Courtesy NASCAR

Photograph Courtesy NASCAR

Photograph Courtesy NASCAR

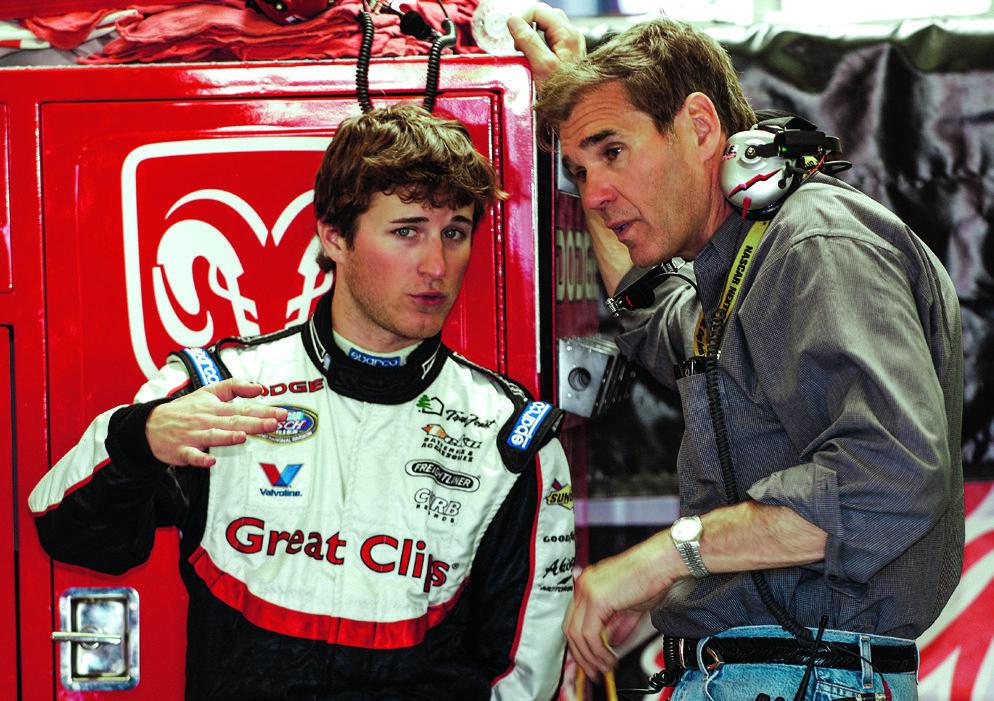

Evernham quit to become a team owner late in the 1999 season, when Dodge came calling with an offer he couldn’t refuse. The brand needed a leader for its Cup program, so the company wrote him a massive check to build his own team. He tested the water in 2000 with three races for Casey Atwood, then jumped into thedeep end in 2001 with a full season for Atwood and veteran Bill Elliott, whom Evernham still teams with in some vintage races.

In eight years as a team owner, Evernham won 13 races in 492 starts, with the best season coming in 2006, when driver Kasey Kahne won six races. Kahne also won five races for Evernham in the Xfinity series. Those weren’t the kind of numbers Evernham was hoping for, but with total winnings in the two NASCAR series adding up to about $55 million, it paid the bills.

In 2007 George Gillett, former owner of the Harlem Globetrotters, bought in as an investor, and soon the team merged with Richard Petty Enterprises. Evernham sold out: It wasn’t fun anymore.

Since he retired as team owner and crew chief, Evernham has become a professional dabbler–and that’s just the way he wants it. He experimented with being a dirt track owner, consulting for some NASCAR teams, developing a museum, and working on a land-speed-record car for drag racer Doug Herbert. He also designed and built the Ghost, a blue-and-white 1936 Chevrolet body perched upon a tube-framed chassis: part modified car, part Trans-Am car and part NASCAR Cup car. The engine is an injected 850-horsepower Chevrolet V8. Evernham has raced the car in some historic events and drove it at the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb last year as a rookie, clocking a time of 10 minutes and 11.344 seconds, fast enough to win the Exhibition class.

He’s also carved out a solid broadcasting career, both as a race commentator and host of his own shows, including “AmeriCARna” that aired on Velocity. NBC Sports broadcasts his current show, “Glory Road,” where he and his guests explore one notable race or motorsports event per episode. He also works with Autogeek, the car care company owned by former IndyCar head Tony George, and has a personal services contract with Valvoline. Oh, and last year he bought JRi Shocks, the North Carolina-based racing suspension company.

Photograph Courtesy NASCAR

Photograph Courtesy Rusty Jarret/Getty Images

Photography Credit: Rupert Berrington

Photography Credit: Rupert Berrington

Now, back to Evernham’s Corvette and why he considers race car driving a little bit of unfinished business.

Evernham was born in Hazlet, New Jersey, on August 26, 1957. As a typical racer, he gravitated as a kid toward the cars he saw competing on Saturday nights at his local tracks. And in New Jersey, those cars were modifieds: low-slung, V8-powered cars with chopped-down bodies from Ford Pintos or Chevy Vegas (before they began wearing their own flat-sided aluminum bodies).

“George Gillett, former owner of the Harlem Globetrotters, bought in as an investor, and soon the team merged with Richard Petty Enterprises. Evernham sold out: It wasn’t fun anymore.”

Modifieds were huge in the Northeast. They were fast and they were dangerous. The cover story of the August 1990 issue of Berggren’s Stock Car Racing was “What’s killing the modified drivers? An in-depth investigative report.”

Ray Evernham was a modified driver, and a good one. He raced them in high-profile NASCAR Whelen modified races at Martinsville Speedway as well as little bullrings like Flemington Speedway and Wall Stadium back home in Jersey. He was racing against some excellent drivers, like Jimmy Spencer, Brett Bodine and Mike Stefanik.

“You don’t make those shows unless you are very fast,” Berggren recalls. “And Ray was making the shows.”

Even though Evernham was working as the chassis specialist for the Roger Penske/Jay Signore-owned IROC series, he continued to race, even after he opened his own race preparation shop in New Jersey.

But everything changed on May 18, 1991. Flemington, a fast, five-eighths-mile dirt oval track, had recently been paved, and now it was even faster. Evernham backedhis modified into the Turn 4 wall so hard that his head made contact with the roll bar, knocking him unconscious. He was hospitalized with a serious injury to his brain stem, putting him out of commission for more than a month.

On June 29, Evernham returned to Flemington and won a 30-lap modified feature inTom Park’s fast No. 2P car. It was emotional, but it was also the end. The brain injury had affected Evernham’s ability to drive, including his depth perception. With the win at Flemington he was able to go out on his own terms, but he knew that his future in racing would not be behind the wheel.

As for Flemington, Evernham’s crash and others led the track to install foam blocks in the corners, early versions of what would become SAFER barriers on larger tracks. The facility operated from 1915 to 2002, and when it closed, it was America’s longest-running Saturday night short track. There’s a Lowe’s store there now.

Evernham hasn’t been able to trace the complete history of his Corvette, but he knows it’s been a vintage racer for quite a while, spending time in Phoenix before eventually being acquired by Tony Parella, owner of the Trans Am series and theSportscar Vintage Racing Association.

“Believe it or not, we haven’t done that much to it,” Evernham says. “The rules are fairly strict to remain in a production class, plus I don’t know that much yet about Corvettes.” They’ve worked on the brakes and the suspension and attended to a lot of safety needs.

“It’s humbling. I’m almost 62, and there are guys out there 10 years older who can whip my butt on any Sunday.”

The car has aluminum heads, a 3.55:1 rear end, and a four-barrel carburetor. It runs on Goodyear Blue Streak tires, 8-inchers up front and 10 in the back. Thetransmission is a four-speed Jerico-style, for which Evernham runs a weight penalty. The basics of the car, he says, “are pretty stock.”

He bought the Corvette for one race, but now he’s having too much fun to sell it. In2014, the SVRA started the Indy Legends Pro-Am race, which paired amateurs with IndyCar racers at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. In September 2018 another SVRA event debuted at Virginia International Raceway, on behalf of Ignite, theAutism Society of North Carolina’s community center for young adults with high-functioning autism or Asperger’s syndrome. Ignite was founded by the Evernham Family Racing for a Reason Foundation.

Evernham knew he wanted in, and the Corvette was available, so he bought it and talked veteran road racer Boris Said into teaming up with him for the race. They won it outright, beating such legends as Bill Elliott, who finished second, and Todd Bodine, Ron Fellows, Al Unser Jr. and Greg Biffle, who paired with Scott Hackenson in a yellow 1967 Ford Mustang to win the small-bore class.

Evernham has run several races in 2019, including HSR’s Sebring Spring Fling and the Mitty at Road Atlanta.

He tells us he’s having a ball, “but it’s humbling. I’m almost 62, and there are guys out there 10 years older who can whip my butt on any Sunday. It’s really challenging. I don’t have that much experience on road courses, and I’m having a lot of fun learning. Some of the drivers are pretty damn good on a road course, and they’re taking me to school.”

Vintage racers are “wonderful people, a wonderful group,” he continues, “and it’s much more relaxed. Everybody is competitive, but socially it’s all about having a good time with our cars.” Pro racing “is just too intense,” Evernham says. “I had 40 years of that. Now I just want to have some fun.”

Photography Credit: Dave Green

Photography Credit: Patrick Tremblay

Photography Credit: Dave Green

View all comments on the CMS forums

You'll need to log in to post.